|

Please visit lgbtfunders.org to learn more about our current programming and ways to support racial equity in your grantmaking. |

|

|

|

Understanding the Elements of Structural Inequality |

|

Synthesizing years of scholarship and analysis

Over the years, a range of leading intellectuals and activists have paved the way for how we understand the nature of racial inequality—its roots, its historical manifestations and its relationship to present day disparities. To support foundation leaders interested in this subject matter, this slideshow teases apart and illustrates the various aspects of these theories. The ideas in this presentation are taken from nonprofit publications, journal articles and various online sources.

Thank you: Structural racism theorists

Funders for LGBTQ Issues would like to thank the many nonprofit organizations that have helped our sector understand the sources and manifestations of structural racism. This presentation draws specifically from The Aspen Institute, the Kirwan Institute for the Study of Race and Ethnicity at The Ohio State University and the Applied Research Center.

Thank you: Philanthropic thought leaders

Additionally, our slideshow relates the wisdom offered by numerous philanthropic groups that have helped foundations understand where issues of race, class, gender, sexuality and gender identity fit within their grantmaking strategies and their internal operations. This presentation draws specifically from the Philanthropic Initiative for Racial Equity, the Center for Social Inclusion, the Diversity in Philanthropy Project and the Race Matters Toolkit from The Annie E. Casey Foundation.

Thank you: Social justice leaders

Finally, these concepts would be nowhere without the thousands of individuals and organizations, across generations, who have tackled these complex questions—and given us explanations, interventions and solutions. This presentation borrows from two organizations in particular: the Providence Youth Student Movement in Providence, Rhode Island and the Center on Race, Poverty and the Environment in San Francisco, California. (For additional insights, scroll through the various perspectives compiled in this toolkit.)

Describing, comparing and understanding

Few would disagree that taking theory into practice is a complicated endeavor. How do we take complicated sociological theories, which often float above us like helium balloons, and give them practical strings that grantmakers, policy makers and nonprofit leaders can grasp? This slideshow responds by providing a step-by-step explanation of the key concepts that frame conversations about race in this country— with an eye to its effects on populations dealing with barriers on multiple levels, such as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer communities of color.

"Race-neutral" vs "race-conscious" approaches

Among these prevailing frameworks, the starkest contrast can be seen between approaches that name race explicitly ("race conscious" approaches) and those that do not ("race neutral" approaches). The omission of race in race neutral approaches can be the result of a well-intentioned oversight, or a deliberate strategy to lead with a factor that's assumed more salient or relevant to the issue at hand—such as poverty or health risks.

A lost opportunity to uncover racial disparities

However, in many instances, removing race from the question is a calculated decision, such as the "affirmative action" debate where opponents argue for the removal of race from consideration in policies that range from employment and education to public contracting and health programs. Whether intentional or not, most race neutral approaches are characterized by their explicit omission of race in how they articulate both the problem and the solution—and what ultimately gets lost is an ability to identify whether racial disparities are even occurring.

Vast evidence of racial disparities

In contrast, race conscious advocates denounce "race neutral" approaches as anything but neutral—the evidence is in the numbers. Vast research shows that people of color experience unequal opportunities in health and wellness, education, income security and civic participation, among other areas. Further, these disparities are pronounced for people living with multiple identities, such as Native/Two Spirit communities, transgender people of color, and gay Latino men (as a few examples). A race conscious approach seeks to understand the reasons behind these disparities.

Naming race explicitly to deal with racial barriers

Additionally, a race conscious approach acknowledges that reducing these disparities requires race-explicit interventions such as targeted recruitment efforts for diversifying an institution or Spanish-language materials for reaching monolingual audiences, as two examples. Further, a race-conscious structural solution for addressing poor educational outcomes would consider the level of funding going to schools in communities of color. In general, any effective race conscious approach must heed the advice of the affected community—communities of color have the most wisdom on issues affecting their lives and the relationships to affect community-wide change.

Grantmaking with a racial equity lens

These are lessons that transfer nicely to the philanthropic sector. To understand how race and ethnicity has shaped "experiences with power, access to opportunity, treatment, and outcomes," a foundation leader could follow a few steps, including: "analyzing data and information about race and ethnicity; understanding disparities—and learning why they exist; looking at problems and their root causes from a structural standpoint; and naming race explicitly when talking about problems and solutions." Source: GrantCraft, Grant Making with a Racial Equity Lens (New York: GrantCraft and Philanthropic Initiative for Racial Equity, 2007

Diversity and inclusion

For many in the public and private sector, including foundations, "diversity and inclusion" has become a popularized entry point. It's an affirmation that our communities are becoming increasingly diverse and our grantmaking strategies must speak directly to this multicultural world. However, because of widespread disagreement regarding its definition and purpose, the "diversity and inclusion" frame takes on different meanings from institution to institution.

The "inescapable fact" of diversity

In philanthropy, "diversity and inclusion" primarily concerns itself with diversifying the demographic composition of a foundation's staff and trustees, as a means of diversifying the character of its grantees and, ultimately, the field. Proponents of "diversity and inclusion" routinely point out that our rapidly globalized world has spurred major demographic shifts and made diversity an "inescapable fact" in our country. Foundations—they argue—should reflect this new composition.

Multiple perspectives = more effective grantmaking

In a philanthropic context, the diversity frame also reasons that the many faces of a diverse community should be represented as decision-makers at foundations. Diverse decision-making bodies lead to multiple perspectives, and multiple perspectives improve innovation, reduce groupthink and are more likely to contextualize the diverse experiences of a community and solve entrenched, complex social problems. In essence, diversity enhances foundations, while also providing opportunities to marginalized populations that were historically barred from positions of institutional authority.

The limitations of "diversity and inclusion" approaches

However, its malleable definition means that "diversity" is often defined too narrowly or too loosely. Narrow definitions leave out entire categories of people who are often rendered invisible, such as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer people. And loose definitions of diversity—which prioritize the benefits of multiple opinions—conflate categories associated with inequality (people of color, poor people) with categories defined that merely suggest difference (political partisanship, personality type). It assures a room full of people that everyone's perspective matters yet incorrectly infers that everyone's perspective is equal.

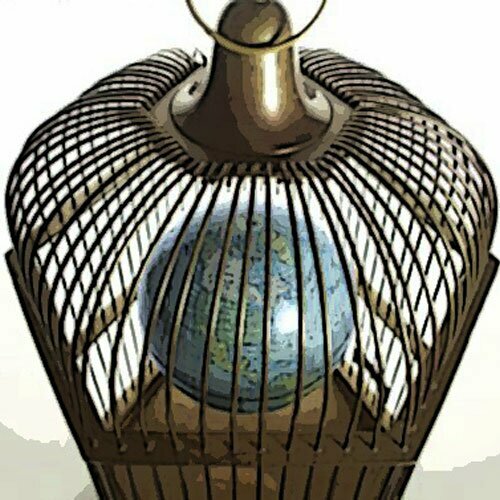

The bird in the birdcage metaphor

Philosopher and feminist theorist Marilyn Frye proposes that we think about the interlocking structures that shape our lives through a "bird-in-a-birdcage" metaphor. Too often, policy makers, program staff and grantmakers fixate on a few bars trapping the bird, yet remain oblivious to the many other bars of the cage. More importantly, from a structural standpoint, they overlook the connectedness of multiple bars that prevent the bird from flying—how each bar reinforces the rigidity of the next one.

Step back and see the role of public policies

But if we step back and look at the totality of the cage, we begin seeing how these bars reinforce each other to confine the bird. For starters, we see the effects of public policies at the local, state and federal level—or the policies we enact within our own institutions, race neutral and otherwise. Many of these policies have accumulated across generations, creating long-term, seemingly intractable, consequences, such as the disproportionate incarceration rates among African Americans.

Step back and see the impact of institutional practices

We also see the by-products of institutional practices—many of which appear race neutral yet lead to unequal opportunities for communities of color. An institution that places graduate level requirements on management level positions might see fewer people of color candidates, given the differential access that people of color have to higher education, pronounced at the master's and doctoral levels.

Step back and see all those cultural representations

Or we might see how cultural representations, largely through various media outlets, become the coded cues through which people interpret their lives or government interventions. For LGBTQ people of color, who deal with various derogatory images about people of color and LGBTQ people, the severity of these representations intensifies.

Step back and see the influence of dominant values

Finally, a panoramic view of the birdcage would reveal how dominant norms and values embedded in the mainstream—including the widely held belief that any of us can prosper if we work hard—overshadow the fact that significant barriers exist to achieving similar outcomes across racial groups, even with the same level of effort.

The Aspen Institute: A structural racism framework

The Aspen Institute offers a framework that breaks out the various dimensions of "structural racism" into distinct parts. It teases apart the specific ways in which structural racism operates, which can help any foundation leader relate to the subject matter by connecting the dots one area at a time. Because conversations about racial inequities too often ignore LGBTQ communities of color, we include examples that bring to life the realities of these populations.

Step 1: The shifting meaning of race

Understanding how race has been defined for a given community is a necessary first step in a structural analysis. Because race is a social construct—not a fixed, biological reality—definitions of race shift over time and across place. For example, the racial/ethnic categories used by the U.S. Census today are very different from the ones used decades ago.

Race = power = racial discrimination

Yet while race is a social construct, racial discrimination is an empirical reality: data repeatedly reveals widespread disparities among people of color. Historically, racial categories have been ascribed political and economic power—and this has ultimately meant widespread discrimination for communities of color, often in the most insidious, less detectable, ways. And for communities dealing with multiple barriers, such as LGBTQ communities of color, the disparities widen.

An example: Tucson news story and immigration

This January 2009 news story from the Tucson Citizen in Arizona describes a federal proposal to provide health coverage to "legal" immigrants and their children. To understand how race has been defined: (1) think about the connotations of the term "illegal"; (2) recognize the limitations of a policy that excludes undocumented immigrants, where poverty and family health concerns are profound; (3) consider that Tucson borders the Sonoran Desert, where every year thousands of Latin American immigrants travel into the U.S., often dying of malnutrition along the way; and (4) look closely at the imagery in the photograph—the race and class inferences of the people profiled. What explain the conceptual disconnect?

Step 2: Intersectionality

A racial equity lens should always be used in concert with other lenses, such as class, gender, sexuality, gender identity and expression, and age (among others). One reason is that many people live with multiple identities—such as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer (LGBTQ) people of color—and in turn experience multiple barriers. These compounding barriers create a heightened vulnerability and lead to wider disparities. Another reason is that the character of racism shifts depending on the population and the context: the barriers facing Two Spirit communities throughout Colorado will be different in many ways from those facing queer transgender people of color in different parts of California. Specificity is key.

Using both diversity and structural lenses: LGBTQ youth of color

It's also important to examine what intersectional can mean at the structural level, across institutions—not simply the individual and interpersonal levels. For example, a policy maker concerned about higher drop-out rates among LGBTQ youth of color might use a diversity lens to examine how LGBTQ students of color deal with school climates characterized by homophobic, racist, sexist and transphobic harassment—across multiple identities. She might also use a structural lens to question why students of color in this country tend to be concentrated in schools with fewer resources. Interventions that deal with both climate issues and broader resource failures will better address these outcomes.

Step 3: Historical advantage and disadvantage

How have our histories—in various parts of the country, across populations—led to the injustices we see today? Why do communities of color continue to experience fewer opportunities and poorer outcomes? A structural race lens reviews the historical advantages that were often denied to people of color in this country, as well as the net effect of these disadvantages in the long-term. As one example, research continues to show significant differences in wealth between white and black households. Less wealth among black communities can be explained by forebears who, for generations, were targets of discrimination, relegated to low-paying jobs with less savings potential, and denied housing—all central to the accumulation of investments, capital assets and savings.

The geographic footprints of inequality

Historical disadvantage plays out at various geographic levels. This map displays U.S. counties that are disproportionately African-American—located largely along the hurricane belt. Historians point out that a history of slavery, failed reconstruction and weak civil rights law kept African Americans in harm's way. And when Hurricane Katrina hit, subsequent studies found that 75 percent of New Orleans' damaged areas were inhabited by blacks, as opposed to 25 percent by whites; one explanation offered was that whites were more likely to live in elevated (less affordable) areas of the city. Worse, climate change experts note that the number of hurricanes—and their severity—has dramatically increased in the last century.

Step 4: Dominant norms and values

It's difficult to construct arguments that relate the unequal effects of these histories—and propose solutions at the structural level—when so many Americans believe that every person is responsible for his/her own life, and with enough hard work, any of us can attain our dreams. In a President Obama world, these value-laden arguments have profound power. Yet these dominant values—personal responsibility, individualism and meritocracy—ignore research that repeatedly shows how communities of color experience fewer opportunities for a better life, even with the same level of effort. If we're presumed to be in charge of our own fates, how do we build public support for solutions that move beyond individual incentive?

Conflicting values across communities

Communities of color are affected by dominant national values of individual responsibility as well as the values, traditions and practices of their own racial/ethnic communities. When the values of one's community are at odds with one's aspirations or one's identity, it can lead to a sense of isolation, even rejection. LGBTQ people of color often must navigate communities and spaces replete with ignorance, stigma and discrimination based on various parts of their identities.

Example: Southeast LGBTQ youth & immigrant families

For example, the Providence Youth Student Movement (PrYSM) works with Southeast Asian youth and their families, many of which came from countries such as Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia—nations devastated by war, genocide, political repression, natural and economic disasters. Southeast Asian LGBTQ youth, as part of these immigrant families, struggle with dominant national values that stigmatize immigrants who are undocumented, as well as the anti-immigrant backlash from the general public. Within their own communities, many Southeast LGBTQ youth are encouraged to marry family members from their homelands for financial reasons, or out of tradition. The stressors of both value systems create a heightened isolation.

Example: School climates for LGBTQ youth of color

It doesn't help that LGBTQ Southeast Asian youth navigate a school system with constant harassment and verbal attacks. According to GLSEN, 80% of LGBTQ youth of color regularly hear homophobic remarks in school; 70% hear sexist remarks; 60% hear trans-phobic remarks and 48% hear racist remarks.

Example: Mental health among immigrant families of color

Traumatized at school, LGBTQ Southeast Asian youth return to families where (according to PrYSM) 70 percent have been diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder and 75 percent suffer from clinical depression. Mental health concerns about Southeast Asian families is widespread. Living in families shaped by geopolitical devastation can mean that the trauma is passed on generation from generation.

Example: Poorer educational outcomes

Given the magnitude of these stressors, and the overall lack of support systems for LGBTQ Southeast Asian youth, PrYSM reports that high percentages of Southeast Asian youth drop out of high school.

Example: Heightened vulnerability

As opposed to 6 percent of white high school students nationwide.

Step 5: Stereotypes & cultural representations

How, then, do these stories get shared? Building popular support for initiatives that address injustice is complicated when you take into account how stereotypes and biased cultural representations shape our individual perceptions. Negatives stereotypes or virtual invisibility—about people of color, women, LGBTQ people and others—have become popularized, dominant and enduring, reinforced through the media and in everyday interactions. For people of color of all sexualities and gender identities, it creates a sense of failure and hopelessness. And for people who believe we are each responsible for our own fate, it creates a sense of entitlement and superiority.

Step 6: Maintaining social hierarchies & segregation

So what happens when these two camps come together to articulate solutions for complex, social problems? In most instances, they don't. Demographic studies have repeatedly shown that racial segregation still typifies our country, cities and neighborhoods, our schools, our job industries and our social networks. When diverse communities don't interact with one another, it creates a "psychological segregation" where we know little about one another and instead rely on stereotypes to inform our thoughts and actions.

Opportunity as a geographic phenomenon

For people of color, segregation has meant being relegated to areas with few opportunities for advancement. The Kirwan Institute for the Study of Race and Ethnicity uses mapping techniques to illustrate the "geographic footprint of inequality." A person's housing and location, given the character of their surroundings, can dictate: the quality of schools children attend; the quality of public services; access to employment, transportation and health care; and exposure to environmental risks. A large body of research has found that communities of color tend to be concentrated in regions where these offerings are fewer and of lesser quality—which ultimately dictates their life chances.

Example: Environmental racism

The well documented practice of placing hazardous industrial sites in communities of color/low income communities fits within the purview of "environmental racism." Here, a structural racism lens helps illustrate why factories are so often placed in communities of color. A business owner who wants to build and place a new factory would use three business-savvy criteria that appear race neutral at first glance. First, he would look for an area zoned for industrial purposes—and find that many industrial sites are located in communities of color. History shows that all around the country, white-led decision-making bodies for years "down-zoned" communities of color for industrial purposes. Source: "Structural Racism, Structural Pollution and the Need for a New Paradigm" Journal of Law and Policy (Vol 20)

Example: Environmental racism (cont.)

Second, if he's seeking an area located next to a freeway for transportation purposes, he would also find that these areas are typically in communities of color. For decades, urban planners ran freeways through relatively stable communities of color. Third, he would consider land value and find that more affordable land is often found in communities of color. Historians have documented how white Americans regularly paid more to not live near communities of color—and over time, land in communities of color depreciated. A tenet of structural racism: racially disparate outcomes do not require overtly racist individual actors. Source: "Structural Racism, Structural Pollution and the Need for a New Paradigm" Journal of Law and Policy (Vol 20)

Progress and retrenchment

Progress in one area (i.e. a policy encouraging "affirmative action" programs in state universities) is offset by retrenchment in another area (i.e. a Supreme Court ruling that limits the usage of race in admissions). Historians have documented how civil rights law, established primarily in the Civil Rights Act of 1964, has been gradually eviscerated by Supreme Court rulings, state and federal policies, and a growing belief that racism has been rectified. Further, the agencies charged with regulating civil rights abuses do little to protect people of color. Of the 150 related complaints filed with the Environmental Protection Agency since 1992, the agency has never once ruled in favor of the complainant. Source: "Structural Racism, Structural Pollution and the Need for a New Paradigm" Journal of Law and Policy (Vol 20)

Step 7: Racialized public policies

Ultimately, our country's opportunity arenas—from schools to government to mass media—produce and reproduce racial disparities. And in many cases, these disparities occur through "race-neutral" policies: Research shows that schools with higher percentages of white students have (1) higher per-student spending (which means smaller classrooms, more teacher attention and more resources for school activities) and (2) more Advanced Placement courses (which means higher rates of college advancement, particularly to elite colleges). Without naming race in the problem or the solution, schools with higher concentrations of students of color see fewer educational successes.

Step 8: Racial disparities & ongoing racial inequality

And the overall result is that communities of color fare worse across all areas, from health and education, to civic engagement and the labor market. Over generations, their lives become portraits of depleted opportunity, shortened life spans, crushing poverty, poor health outcomes, verbal and physical violence, and widespread discrimination. A core difference between a race conscious approach and a race neutral approach is whether these racial disparities are even being investigated. Because without data on these disparities, it's impossible to identify the root problems, much less devise solutions that reform the very structures we inhabit.

Schedule a presentation for your colleagues

Interested in exploring how these ideas relate to your foundation? Funders for LGBTQ Issues would like to offer ourselves as a resource to you and your foundation colleagues. Already, we've successfully presented on structural racism and LGBTQ issues to hundreds of foundation leaders, practitioners and activists around the country—from Arizona to Minnesota, from New York to Los Angeles. Please contact us to schedule a presentation and workshop tailored for your foundation's needs. |

|

1 / 43 (Part 1: Slides 1-19) (Part II: Slides 20-43) |

|

HOME

Content and images © 1997-2021 Funders for LGBTQ Issues. All rights reserved.

Funders for LGBTQ Issues - 45 W 36th Street, 8th Floor - New York, NY 10018-7633 - 212.475.2930 - fax 212.475.2532 -